Part One: Background and Context

Preamble

The Canadian context

Key concepts and their relevance

Challenges for members of underrepresented groups

On failure

Part Two: Tangible Suggestions to Support Inclusion and Diversity

Departmental culture and relationships

Hiring, promotion/tenure, and professional development

Research

Conferences and seminar series

Teaching

Service

Final considerations

Equity resources

Part One: Background and Context

Preamble

Background

There are good reasons to believe that many Canadian philosophers consider diversity and equity important to them personally and believe that advocacy for diversity and equity is a norm in professional philosophy (Nelson et al., 2018). This document provides concise, tangible suggestions about how to foster greater inclusion and diversity in Canadian Philosophy. The British Philosophical Association (BPA) and the American Philosophical Association (APA) have both created similar documents. Our intent is to supplement these resources rather than replicate them, while foregrounding Canadian interests and values. While the APA's Good Practices Guide is a comprehensive recommendation for best practices in professional philosophy generally and the BPA/(UK)SWIP's Good Practice Scheme is a rather more accessible set of recommendations to ameliorate disparities in gender representation, the present document offers concise suggestions and heuristics directed at addressing the underrepresentation of women, people of colour, people with disabilities, Indigenous people and genderqueer folks in the profession as well as the inclusion of their interests and perspectives in the content of our work. The hope is to extend philosophy so as to make it more representative and inclusive in its practice, pedagogy and in the professoriate.

Structure

We recognize that different people will be more or less familiar with the fundamental ideas underlying these proposals and may or may not have given much thought to the specific contours and commitments that are particular to the Canadian context. With this in mind we assume no background knowledge but only a good faith commitment to making our discipline more diverse, equitable, and inclusive. The first part of this document provides a very cursory overview of this background, offering brief introductions to key concepts and identifying specifically Canadian considerations that should inform equity policies and practices. This part concludes with the particular challenges faced by underrepresented groups. By necessity, this section cannot be exhaustive and a list of sources with more complete and nuanced information are included at the end. The main body of the document addresses department/institutional culture, research, teaching, and service. The intent in these sections is to offer tangible recommendations for good faith measures whereby members of overrepresented groups can work to make the philosophical community more representative of the diverse publics that we serve. It is not expected that all professors will choose to take on all these measures. Rather, it is hoped that these may become heuristics and norms that can help make our discipline more inclusive.

Critical friendship

The document is offered in the spirit of critical friendship. As defined by the Glossary of Education Reform, "A critical friend is typically a colleague...who is committed to helping an educator or school improve. A critical friend is someone who is encouraging and supportive, but who also provides honest and often candid feedback that may be uncomfortable or difficult to hear. In short, a critical friend is someone who agrees to speak truthfully, but constructively, about weaknesses, problems, and emotionally charged issues." At its best, philosophy can exemplify the virtues of critical friendship. In this document our goal is to bring these strong value commitments and critical practices more directly to bear on our profession.

The Canadian Context

Official multiculturalism

We are a multi-ethnic nation and multiculturalism is often taken to be central to Canadian identity (Foran 2017). As a liberal democracy, Canada is committed to the Millian ideal of a diverse market place of ideas. We do our community and our students a disservice if Canadian philosophy is Eurocentric and colonialist in its perspective. Moreover, in an increasingly internationalized academic environment taking multiculturalism to heart may be a particularly effective way of making Canadian philosophy relevant in the 21st century.

The Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)[1]

The TRC has provided a unique opportunity in Canadian history for all of us--Indigenous, settler, and immigrant--to decolonize our institutions, ideas, and practices. The collaborative character of this process can be expected to stretch professional philosophy in ways that many of us will find challenging. As Canada moves toward recognizing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoplethe need to expand and redefine the content of philosophical research and pedagogy away from its colonialist and Eurocentric roots can be expected to become more urgent (see also Bill C-262).

Education is an important part of the TRC's Calls to Action. Key relevant recommendations, as stated by Universities Canada, are included below:

1. Ensure institutional commitment at every level to develop opportunities for Indigenous students.

2. Be student-centered: focus on the learners, learning outcomes and learning abilities, and create opportunities that promote student success.

3. Recognize the importance of indigenization of curricula through responsive academic programming, support programs, orientations, and pedagogies.

4. Recognize the importance of Indigenous education leadership through representation at the governance level and within faculty, professional and administrative staff.

5. Continue to build welcoming and respectful learning environments on campuses through the implementation of academic programs, services, support mechanisms, and spaces dedicated to Indigenous students.

6. Continue to develop resources, spaces and approaches that promote dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

11. Recognize the importance of providing greater exposure and knowledge for non-Indigenous students on the realities, histories, cultures and beliefs of Indigenous people in Canada.

12. Recognize the importance of fostering intercultural engagement among Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, faculty and staff.

Section 15 of the Charter

Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms is an important symbol of national identity in which the majority of Canadians take considerable pride (Environics Institute, 2010). Section 15, "Equality Rights," endorses a vision of equality that informs the current document. The Charter not only protects people from "discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability [or sexual orientation]," but also "does not preclude any law, program or activity that has as its object the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups" (Constitution Act 1982). This document is written on the presupposition that in the discipline of Philosophy, although it is necessary to endorse and normalize practices that protect students and scholars from discrimination, it is insufficient given the magnitude of the current problems. We must also endorse and normalize practices that have as their object "the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups" (Constitution Act 1982). This requires a shift from non-discrimination to anti-discrimination.

Key concepts and their relevance

Implicit bias

Attitudes or stereotypes that affect our judgement and actions unconsciously. Studies in social psychology suggest that our implicit biases may be contrary to our avowed commitments and that those with strong social justice commitments may be least amenable to recognizing and ameliorating their own bias (see Greenwald and Schwartz 1998; Saul 2013; Kelly and Roedder 2008)

Stereotype threat

Stereotype threat is a situational predicament identifying the ways in which anxieties about conforming to negative stereotypes tend to impede the performance of members of negatively stereotyped groups. Stereotype threat is particularly potent when group membership has been made salient in a particular context even if the negative stereotype is not mentioned (for instance, if a professor says"Good luck, ladies," to the women in their class at the beginning of a math exam) (see Schouten 2015; Steele, Spencer and Aronson 2002).

Moral licensing

Doing something that positively affects one's self-image in some respect tends to make one less concerned about behaving immorally in that respect. For example, doing something that makes one feel less sexist, by, say, including more women on one's reading list, may make one less concerned about speaking over women at meetings. A more troubling example, though no less familiar, is when someone who persistently sexually harasses women also consistently promotes the careers of female students (see Monin and Miller 2001; Blanken, van de Ven and Zeelenberg 2015),

Institutional discrimination

Policies and practices that tend to work in favor of a dominant group and systematically disadvantage another group. These norms can be particular to an institution but many such norms are embedded in the existing structure of society and reverberate through most institutions in that society. For instance, the criminalization of people of African descent and Indigenous people, not only increases the likelihood of their entering the criminal justice system, but affects their experiences of the education system, their ability to secure lodging and bank loans, and so forth (see Pincus 1996).

Epistemic injustice

The recognition that not all people are identified as equal knowers. Members of some groups have certain types of knowledge systematically withheld from them; members of other groups have their testimony systematically discredited; members of other groups are silenced by there being inadequate resources available to them to make themselves understood. Philosophy should be a resource for combating epistemic injustice but is often experienced as a prime perpetrator of epistemic injustice (see Fricker 2007; Medina 2011 and 2012; Dotson 2012 and 2014).

Intersectionality

The recognition that axes of oppression are not additive but often interact and create specific types of challenges and barriers that are difficult to anticipate or understand from external perspectives or unidimensional approaches to oppression (see Crenshaw 1989; Cho, Crenshaw and McCall 2013).

Tokenism

Efforts to create more inclusive in teaching, research, and service can result in tokenism--"the practice of making only a perfunctory or symbolic effort to do a particular thing, especially by recruiting a small number of people from under-represented groups in order to give the appearance of sexual or racial equality within a workforce" (OED, s.v. tokenism). Worse yet the fear of being accused of tokenism can deter people from taking action to diversify or become more inclusive. Note that efforts to sincerely and substantively include and engage colleagues, scholarship and scholars does not tokenize. Particularly when inclusion is of members of underrepresented groups themselves who are being asked to give up their time, people are encouraged to follow the inclusion with influenceheuristic described below (see Niemann 2016).

Academic freedom

"Academic freedom is a distinctive class of freedoms possessed by scholarly personnel of certain types of educational and research institutions by virtue of the social role that they fulfill. It's an umbrella term for a number of freedoms, including the freedom to design lines of inquiry, choose research topics, design methodologies, teach as our expertise guides us. Students have the freedom to learn as their conscience and curiosity guides them. Freedom of expression--often conflated with academic freedom--comes only at the end" (Dea 2018). The flipside of academic freedom is accountability for the activities that we freely pursue and the ideas that we express.

Types of inclusion

Of actual people: Perhaps the most important type of inclusion from which many of the other types of inclusion often flow is the inclusion of members of underrepresented groups. It is an error, however, to think that if one does include members of underrepresented groups in one's department as faculty members, students, and visiting scholars that one's work is done or to think that, if one is unable to achieve these goals, nothing more can be tried.

Of perspectives: In research and in classroom contexts one can include the perspectives of underrepresented groups by not merely addressing issues that pertain to these groups but also statements and claims made by members of these groups. Note: this can be fraught as many of the nuances and complexities that pertain to these issues, the groups, and those taken to represent them may not be obvious to people without the relevant experience or expertise. Philosophical work that takes on the issues or perspectives of a particular underrepresented group can often be less fraught, assuming that they are recognized as legitimate scholarly contributions in the relevant subdiscipline.

Of philosophy by: In research and in classroom contexts it is important to include philosophy by members of underrepresented groups.

Of philosophy in the tradition of: This is particularly salient when it comes to including philosophy outside the Anglo-American and European traditions.

Relationships between types of inclusion: Often these types of inclusion line up, as when women who work in feminist philosophy research issues that particularly pertain to women and teach the feminist philosophical tradition as one reaching back to Mary Wollstonecraft and Anna Julia Cooper. And often they don't, as when a philosopher with a disability and of Asian descent works in analytic epistemology. All types of inclusion matter and individuals and departments are tasked with doing the best they can along each axis.

Challenges for members of underrepresented groups

Much discrimination is inferiorizing. For instance, women's intellects are sometimes tacitly assumed to be inferior to men's, their time is considered less valuable, and they are expected to be nurturers in the workplace (regardless of their job descriptions). Discrimination is also alienating as there are countless small ways, micro-aggressions, by which it is tacitly asserted that those discriminated against do not belong (Haslanger 2008).

Members of underrepresented groups are often encouraged to speak on behalf of that group, or study or teach philosophy pertaining to that group. For instance, one may simply assume that a given woman will want, and be qualified, to teach feminism, regardless of the level of training that has had in this subdiscipline. While for certain groups, there is a correlation between being a member of that group and being interested in the philosophical issues that pertain to them (consider the predominance of women in feminist philosophy), this is not always the case and should not be assumed for any given individual member. Similarly, while members of underrepresented groups often have valuable perspectives particular to that group membership and specific expertise pertaining to it, any given person may not; and even if they do they may not wish to share it. The basic point is that within any given underrepresented group there is diversity and complexity and one shouldn't make assumptions about how individuals navigate them.

Members of underrepresented groups and philosophers who work in marginalized areas of philosophy often face double standards. When members of underrepresented groups do work on perspectives of, philosophy by, or philosophy in the tradition of their group they find that this work is not seen as real philosophy by many of their colleagues, even when their colleagues have almost no knowledge of the work in question (Dotson 2012). Bafflingly, positions with basically the same ontological commitments or based on very similar arguments will be considered important and insightful if presented from within the philosophical mainstream but be dismissed if identified with a "non-Western" tradition or a marginal philosophical subdiscipline. Philosophers who wouldn't dream of employing one of Hume's ideas without adequate citation, will help themselves to ideas they find in Buddhism without proper research or adequate credit. These attitudes and practices are powerful ways of saying that these philosophers, perspectives, and philosophical traditions do not belong. Such dismissal without adequate information, careful consideration and honest discussion is the essence of prejudice and it is incompatible with the philosophical spirit of critical inquiry and Canadian commitments or, indeed, liberal democracy more generally. (For further insights about the challenges faced by various underrepresented groups see the links below to General Equity Resources; Equity Resources on Gender, on Race, on Non-European Philosophy, on Indigenous Philosophy, on Disability; and Equitable Teaching Resources.)

On failure

The challenges of learning and teaching new and unfamiliar material and sensitively navigating the complexities of addressing issues like colonialism and intersectionality can seem perilous. Nonetheless, it is the right thing to do; our discipline will not become more equitable and inclusive without our making it so. This requires us to be open to changing, generous in our interpretation of each other's actions and motivations, and resilient and attentive in the face of criticism (see note section on critical friendship above).

While we may be inclined to congratulate ourselves for not being, for instance, racist, sexist, ableist, cissexist, classist, or heterosexist, the lessons of social psychology suggest that we probably enact these biases whether we want to or not. Commitment to being anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-ableist, anti-cissexist, anti-classist, and anti-heterosexist entails that we are open to discovering ways in which we enact these prejudices so that we can figure out how to live in ways that better conform to our own values (Bernard and Butler 2014). In this light, failure and disorientation can be seen asmoments of insight that make progress possible (see Harbin 2016).

Part Two: Tangible Suggestions to Support Inclusion and Diversity

Departmental culture and relationships

Negotiating power, sexual harassment, and faculty-student relationships

Most universities have clear sexual harassment policies and clear directions about staff-student relationships. Because of the potential for disciplinary action and the legal ramifications of these situations we advise deference to these policies. We do, however, note that the restrictive character of these policies should not be seen as a reflection of contemporary prurience but a recognition of the abuses of power that often accompany faculty-student relationships.

As a basic rule, people in a professional relationship with a disparity of power, such as professor-student relationships, should avoid romantic or sexual relationships as well as intimate friendships for as long as they are in those professional relationships.

Caregiving and family obligations

Caregiving, both eldercare and childcare, remains gendered in Canadian society. This gender structure can be particularly complicated and challenging when it intersects with other aspects of identity. Departments should attempt to accommodate reasonable requests that facilitate members' ability to meet family obligations; moreover, they should ensure that the burdens associated with such efforts do not fall disproportionately on the shoulders of members of underrepresented groups or otherwise vulnerable members of their departments, such as graduate students and those with limited term appointments. Accommodations include flexible scheduling classes and meetings and supporting requests for leaves of absence. Departments should be equally supportive of men and women taking on the familial burdens of care (and so help women negotiate sexist societal expectations and help men subvert them). Chairs and affected members are encouraged to navigate these issues with support from institutional human resources departments and relevant unions. None of this precludes requiring department members do their jobs.

Hiring, promotion/tenure, and professional development

Hiring

Most universities have had equity hiring policies in place for some time, but they are unlikely to be optimally effective without thoroughgoing support from departments throughout the hiring process. Below are some key suggestions to make hiring more inclusive and diversify departments and curricula.

Just choose: Decide, as a department, to make every effort to hire someone who is a member of a group that is underrepresented in your department. You will then need to define your position, write your ad, and distribute it in ways that help you meet this goal. You may want to discuss your plan with your dean or the university's human resources or equity office to see if you can guarantee the right to advertise the following year should you have a failed search.

Define an inclusive position and be ready to identify non-traditional candidates as filling it: For instance, if you are hoping to hire a woman, given the correlation between doing feminist work and being a woman, it is wise to write your ad so that it clearly includes feminist perspectives in the area of specialization (for instance, "contemporary epistemology, broadly construed"). Even for non-feminist philosophers this can signal a department's commitment to inclusiveness and diversity. If you are simply looking for more diverse candidates for what might sound like a traditional job, be sure to indicate as much (for instance, "political philosophy, broadly construed, including non-Western, disability, feminist, queer, and critical race approaches"). Then actually consider candidates who do political philosophy in non-traditional ways. Remember, Mohandas Gandhi, Mengzi, W.E.B. DuBois, and Iris Marion Young are political philosophers and one can be a real political philosopher, while primarily studying one of these (or many other) figures. Note that philosophers may not have PhDs in Philosophy. Most of us would recognize that someone with a PhD in Classics, from a philosophically-oriented, well-regarded Classics program, who had written a dissertation on the thought of Plato or Aristotle would be a legitimate hire for a position in Ancient Greek Philosophy in a Philosophy Department. Being willing to recognize the possibility of similar disciplinary overlap with other cognate disciplines (such as Indigenous Studies or Religious Studies) may help departments diversify.

Be ready to learn that your presuppositions about certain subdisciplines are flawed. Treating familiar philosophical topics in novel ways often produce insights that go beyond the traditional boundaries of a subdiscipline. Being inclusive requires an openness to rethinking how philosophy circumscribes certain topics and subdisciplines. This need not come at the expense of rigor, but it is incompatible with dogmatism.

Keep interviews professional: Do not inquire about or make assumptions about people's personal lives during the interview process. Candidates can be asked to fill in the appropriate institutional self-declaration of identification. Department members can state their commitment to creating a more diverse and inclusive program and ask how candidates see themselves contributing to doing so. If candidates offer information indicating aspects of their personal lives, such as family status, sexual orientation, or disability status and request relevant information, such as institutional accommodations, department members should provide the relevant information or direct the candidate to the appropriate resource.

Only interview serious candidates: Applying for jobs and preparing for interviews are extremely time-consuming. Interviewing candidates to fulfill equity requirements when there is no real possibility that your department will hire them is unethical, particularly if this involves flying in for an on-campus or APA interview.

Value equity and diversity literacy and practices: Have as a criterion for hiring a candidate that they have good equity and diversity practices. Assess their application materials using an equity lens (for instance, examining syllabi in terms of inclusiveness and diversity in the course content) and ask specific questions during job interviews about their equity practices.

Collectively and consciously watch out for double standards: Implicit biases can lead members of hiring committees to assume the competence of members of over-represented groups while requiring greater evidence of competence and achievement of members of under-represented groups. Some departments address this by explicitly specifying standards for the evaluation of candidates prior to evaluating candidates. (See the BPA/UK-SWIP Good Practices Scheme, "Recommendation: Hiring panels")

Promotion/tenure and professional development

Mentor junior faculty: Whether officially assigned or informally enacted, it is important to mentor junior colleagues in the norms of the discipline and in navigating our institutions. This is particularly important for members of underrepresented groups who often face additional challenges and barriers.

Include interdisciplinarity: People working on perspectives of, and philosophy in, the tradition of underrepresented groups or in other areas of philosophy that tend to be marginalized, such as disability studies or critical race philosophy, often find themselves working in interdisciplinary contexts. Anecdotally, this results in a kind of triple jeopardy as interdisciplinary work is (i) notoriously more time-consuming than disciplinary work, (ii) requires engaging with scholars and individuals outside philosophy, including presenting work at non-philosophy conferences, and (iii) often results in articles that are not (currently) likely to be published in top-tier philosophy journals.

Mentors should be aware of the risks that their junior colleagues are negotiating and offer them support and pragmatic advice about how to do their work in such a way as to be intelligible as philosophy to the relevant decision makers.

Chairs and promotion and tenure committees should be alive to this triple jeopardy and read their junior colleagues' files in this light. They should seek external letters of support from people in their junior colleague's area who are best able to judge the quality of the relevant interdisciplinary venues.

Support (at least, do not penalize) good faith efforts to create more inclusive classes: As noted in the section above, On Failure, the challenges of learning and teaching new and unfamiliar material and sensitively navigating the complexities of a more inclusive curriculum can be perilous. Efforts to modernize curricula can backfire on professors sometimes in totally unanticipated and fairly catastrophic ways. Because of the importance of the early years in the professoriate for developing one's own teaching style, it is particularly important that new professors feel free to explore ways of making their courses more inclusive. It is thus important to assure junior colleagues that such failures, when the result of good faith efforts following good practices in our discipline, will not be held against them but will instead be lauded as classroom innovations when it comes to their tenure and promotion assessment.

Adequately recognize "service work" by members of underrepresented groups to their communities: For some communities, particularly those who are the most underrepresented in our discipline, having one of their members in the professoriate, especially in a core academic discipline like philosophy, is deeply significant. As such, these faculty members may be particularly powerful symbols to the members of this group (and prospective students) that they too belong in philosophy. These faculty members may also get multiple requests to serve this community in ways that are not typically valued by the profession, for instance speaking at community events or serving as a community representative. Chairs and promotion and tenure committees are encouraged to find creative ways consistent with their collective agreements to treat it as a type of research or knowledge translation in their assessments of their junior colleagues and not denigrate it as "mere service." This point can be extended to service work for equity efforts (e.g., MAP, CSWIP, CPA Equity Committee).

Limited term appointments (LTAs): LTAs (sometimes called "precariat faculty") are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Especially when LTAs are members of underrepresented groups, Chairs and permanent department members are urged to ensure that their professional interests are protected. It is noted that LTA positions themselves are often undesirable (as when they are used to permanently take the place of tenure-track positions); so, it may require considerable attentiveness and nuance to oppose the addition or continuation or LTA positions while supporting the people who hold them.

Research

In your own research

We saying: If one uses the term "we" they should consider who is included in that "we." As a heuristic, when using an unqualified "we" one should imagine one is addressing an audience exclusively made up of people from underrepresented groups and intend the "we" to include them.

Appeals to intuition that are just culturally specific dogma: Related to "we saying" is the tendency to identify certain beliefs as "intuitions" that "we all share" when in fact they are just beliefs that are typical in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies (Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan 2010).

Inclusive credit: When the arguments or concepts that one is using or defending have been articulated and employed by non-Western philosophers, philosophers that are otherwise often considered marginal (e.g., feminist philosophers, philosophers of race, queer theorists, disability theorists, etc.) one should read, cite and critically engage that work.

Diversity in your research: Look at your reference lists and consider who you cite. If all your citations are of work by white men this may mean that implicit biases or institutional discrimination are affecting your research. As a heuristic, look to have at least one third of your references by members of underrepresented groups or from non-European or non-mainstream (i.e., feminist, queer, disability, or critical race) perspectives. If you achieve this, aim for half.

Research projects with others

Inclusion with influence (Bunjun 2011, 270): When working in research partnerships one should be sure not to exploit members of underrepresented groups. This includes giving them adequate credit for their ideas and their work and not leaving an unfair share of tedious academic grunt work (such as proofreading or reference checking) to them.

Multiple paths for inclusion: Accommodating people with different abilities and various life complications requires a certain amount of inventiveness and openness. Research projects should be structured to avoid ways of subtly excluding people.

Credit: Questions about credit and authorship for shared projects are often difficult to negotiate. This is further complicated by the fact that senior philosophers, typically members of overrepresented groups, often have professional status and connections that help projects get up-take with audiences and publishers, which incentivizes junior philosophers to work with them. Address questions about authorship and workload explicitly and early with an awareness of the role of status and power.

Journals

Given the importance of the gatekeeping role of journal editors and the prevalence of implicit biases, journal editors should take steps to address discrimination against members of underrepresented groups and support their success.

Desk rejections: As a rule, when they are able to identify authors journal editors should not desk reject members of underrepresented groups or work by philosophers from countries outside the Global North. This is a way of addressing implicit bias.

So, you want to diversify your journal: Over the years, journals acquire reputations for being uninterested or actively hostile towards certain approaches to philosophy or certain groups. Journal editors are encouraged to notice if their journals lack diversity in either their authors or the topics and sub-disciplines that are addressed. Editors of high profile journals have a particular obligation to address this question. Journals that have special issues are well-positioned to address this problem as they can plan special issues that target subjects that members of underrepresented groups tend to publish on or seek guest editors with expertise pertinent to perspectives of, philosophy by, or philosophy in the tradition of various underrepresented groups.

Conferences and seminar series

Seminar series

Diversify your seminar series: Take steps to invite members of underrepresented groups. Aim to have at least one third of the philosophers presenting at your seminar series be members of underrepresented groups. If you achieve this, aim for half.

Ways to compensate if you fail to diversify your seminar series: If you fail to have one third of your seminar speakers be members of underrepresented groups, seek to redress this by inviting members of underrepresented groups as speakers for endowed lecture series and conference keynotes. This has the beneficial side effect of helping members of underrepresented groups achieve academic success.

Conferences

Accessibility in preference to accommodation: A complete guide to hosting inclusive conferences has been developed by CSWIP and can be found here (http://cswip.ca/images/uploads/CSWIP_Accessibility_Working_Group_Document.pdf ). Conference organizers are encouraged to adopt a norm of making their event accessible rather than adopting a norm of accommodation. An accommodationist approach takes for granted and naturalizes as normal the requirements of a certain range of people, while those who have other requirements are expected to make special requests "as needed" that will be treated in a supplementary fashion.

Location: Conference organizers should choose locations that meet basic accessibility requirements, such as wheelchair accessibility and appropriate supports for people who are sight or hearing impaired.

Childcare: Conference organizers should make child care accessible to participants with small children.

Food: Conference organizers should be prepared to accommodate dietary needs and preferences.

Registration: Registration sites can be excellent places to provide conference participants details about the accessibility features of the conference location as well as request further details from participants about additional requirements regarding accessibility, childcare and food.

Financial supports: Conference organizers should make a particular effort to provide financial support for conference travel for members of underrepresented groups when there is good reason to believe that they may not have support for conference travel from their home departments.

Tokenism: Efforts to create more inclusive programs can result in tokenism. As noted above, efforts to sincerely and substantively engage scholarship and scholars does not tokenise. So, if event organizers ask members of underrepresented groups to participate in an effort to diversify their program they should make sure that other participants are able and inclined to sincerely and substantively engage their work (i.e, they are a good fit for the event, not an odd ball outsider).

Teaching

Curriculum

One way that philosophy departments can both diversify themselves and support efforts in their home faculties to diversify is to develop cross-listed courses that serve programs that pertain to members of underrepresented groups (for instance, religious studies, gender studies or Indigenous studies). Such courses should not be seen as alternatives to increasing diversity in the current curriculum. While there is no better way to diversify our curricula than by hiring people who work in areas of philosophy that are currently marginalized (such as non-Western philosophy) treating this work as niche and not part of the core of philosophy proper is still problematic (Garfield and Van Woorden 2016) and the recommendations about content below are informed by this consideration. (Note, many of our programs have at their core subdiscipline-specific survey and history of philosophy courses that are required for undergraduates majoring in Philosophy. With this in mind, weparticularly address these types of courses below.)

Content

Diversity in your course content: If the vast majority your readings in a course are by white men, this may mean that implicit biases or structural discrimination are affecting your pedagogy or it may be that the subdiscipline that you are teaching has been distorted by these prejudices. As a beginning heuristic, look to have at least one third of your readings by members of underrepresented groups or from non-European or non-mainstream (i.e., feminist, queer, disability, or critical race) perspectives.

Be sensitive to your student body: A sincere commitment to the Calls to Action from The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and official multiculturalism requires that many of our courses should have some content from Indigenous Canadian and non-Euro-American sources. However, in times and places where a particular type of racism or other prejudice is especially salient, or where a significant number of students are members of an underrepresented group, professors are encouraged to include content by or salient to members of these groups.

The one quarter heuristic for core survey courses: Of course, not all courses equally lend themselves to the inclusion of diverse perspectives. It may not be obvious how to bring in inclusive perspectives to a logic class. Also, there is, for good reason, an emphasis in core classes on teaching central issues and figures. Nonetheless, in most core survey courses, like epistemology, philosophy of language, philosophy of science, philosophy of religion, metaphysics, political philosophy, and ethics, it is possible to use some authors from underrepresented groups for discussing standard topics and to put aside one quarter of the class for perspectives of, philosophy by, or philosophy in the tradition of underrepresented groups. Sources for inclusive syllabi are listed below.

Look for opportunities to diversify your history of philosophy courses: Depending on how your department structures their history of philosophy courses, non-Western philosophies can be included in some of the survey courses. Some history of philosophy courses lend themselves to the inclusion of diverse perspectives, such as the inclusion of Islamic or Jewish thought in Medieval philosophy courses. However, it is possible to reframe other history of philosophy courses to diversify their content also. Ancient or classical philosophy need not restrict itself to Greece, but can include philosophy from Egypt, India, or China. Courses structured around basic theoretical commitments, like the Rationalists and Empiricists, will find authors in the Indian tradition, for instance, who easily fit in. The inclusion of philosophy by women and issues addressing colonialism are other ways of diversifying courses in the history of philosophy. Sources for inclusive syllabi are listed below.

Comprehensive exams: Comprehensive exams not only reflect a department's implicit view of the core of the discipline but also provides the basis of knowledge from which students draw as they develop as teachers. As such, diversifying the content of comprehensive exams is a particularly effective way of promoting lasting change.

Methods

"We" saying and appeals to intuition that are just culturally specific dogma: Be sure when using a collective "we" in classes that you are not just referring to people like you but you are including everyone who could be in your classroom (i.e., men should be sure to include women, people from the Global North should include those from the Global South, cisgendered people should include transgendered people, and so forth). Similarly, when making appeals to intuition that are supposedly obvious to everyone, ensure that they are not in fact only beliefs that are typical in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies (Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan 2010). Repeatedly tacitly telling students that by "we" you don't mean them and that they don't have philosophically correct intuitions is a way of telling them that they don't belong in philosophy.

Diversify participation: Particularly when participation is graded, it is important to find alternative ways of participating than simply speaking in class. Discussions on course websites or asking students to submit reading reflections prior to class that can then be used to inform class content are ways of supporting the full participation of students who might otherwise find participation intimidating or challenging.

Consider anonymous grading: Anonymous grading has been shown in some contexts to improve the grades of underrepresented groups. Nonetheless, the practice in controversial. One possible model is to initially assign a grade to an assignment anonymously and then offer more specific comments having identified the student. In larger classes, where students are unknown to the grader, anonymous grading is typically preferred as it protects against implicit biases.

Employ inclusive and non-discriminatory language: While this is a shifting target, we should all make an effort to employ non-discriminatory language. So, for instance, we should use gender neutral pronouns where appropriate and encourage (if not require) our students to do so also.

Identify excellence. For various reasons, members of some underrepresented groups have a tendency to underrate their intelligence and capacity even when they receive outstanding grades. When you have a student from an underrepresented group who is an excellent philosopher let them know. If you believe they have the talent to go on in philosophy, tell them so. If they are interested in pursuing philosophy, give them advice on how to do so and direct them to relevant resources.

Service

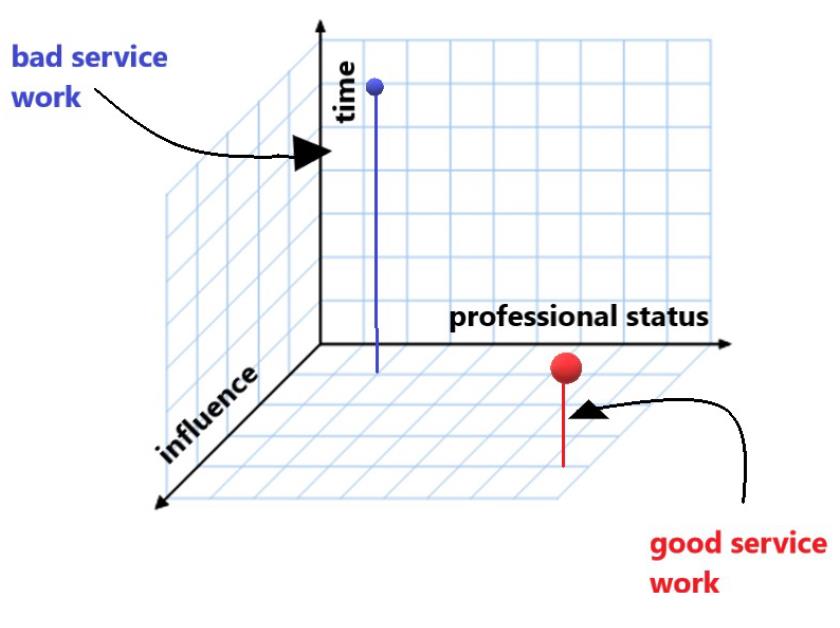

Inclusion with influence

Inclusion with influence is necessary if our equity policies are to be genuinely empowering for members of underrepresented groups (Bunjun 2011, 270 ff.). Colleagues and administrators should support members of underrepresented groups by ensuring they are not disproportionately burdened with service work that is time consuming, has little influence on our discipline, departments and universities, and is of low professional status. At the same time, much of this service work is essential to the profession, our universities, and our departments. This means that senior scholars and members of overrepresented groups must, concomitantly, be willing to serve in these roles.

Judgements of professional status can be made on the basis of the relevance of said service work for tenure, promotion, and professional honors. Judgements regarding influence can be made on the basis of the extent to which the position is a gatekeeper for students, scholars, or scholarship and the extent to which the position offers opportunities to shape the various levels of academic and disciplinary institutions. The contrast should be made with the professional status and influence that would accrue to the scholar should they have the equivalent time to pursue their research. Attention should be paid to work in the service of teaching versus work in the service of research as typically service work addressing research is deemed higher status than that concerned with teaching, though university cultures vary on this point.

|

|

|

Final considerations

What is enough? When can we stop working to make philosophy more inclusive?

None of us can claim to know what a completely equitable and inclusive discipline would look like. Nonetheless, it is impossible to look at our current population and practices and believe we have achieved it. If today our discipline were unshaped by biases and discriminatory structures one would expect the representation of various groups to roughly mirror their representation in the Canadian population, with one half being women, a little over 7 out of 10 philosophers being white, 1 in 20 being Indigenous (Grenier 2017), 1 in 10 having a disability of some kind (Arim 2017) (and so on).

Sceptics often maintain that the current demography of our discipline is merely the side effect of people choosing educational options and careers other than philosophy. This kind of response merely moves the question back one step. After all, people tend to choose options that are good for them, so it merely changes the question to how to make philosophy a better option for members of underrepresented groups.

Try not to make things worse

Each of us has to assess our own skills and personality and decide what we can do to diversify our discipline. If you cannot in good faith follow some of these guidelines see if you can follow others. Minimally, all members of overrepresented groups can make sure that their colleagues do not have to take on an unfair burden of service by stepping up to do important but ungratifying work when needed and they can support rather than deride or block their colleagues' attempts to make the discipline more inclusive.

Equity resources

General Resources

- APA Good Practices Guide http://www.apaonline.org/page/goodpracticesguide

- BPA/SWIP Good Practice Scheme https://bpa.ac.uk/resources/women-in-philosophy/good-practice

- Discrimination and Disadvantage: http://philosophycommons.typepad.com/disability_and_disadvanta/

- Minorities and Philosophy: http://www.mapforthegap.com/

- Directory of Underrepresented Groups in Philosophy: http://www.theupdirectory.com/

- The Unmute Podcast (applied philosophy): https://unmute.squarespace.com/#intro

- University of Ottawa Introduction to Inclusive Practices: http://www.uottawa.ca/respect/sites/www.uottawa.ca.respect/files/accessibility-inclusion-guide-2013-10-30.pdf

- The Deviant Philosopher: https://thedeviantphilosopher.org/

- UP Directory: A Directory of Philosophers from Underrepresented Groups in Philosophy: https://updirectory.apaonline.org/

Gender

- Data on Women in Philosophy: http://women-in-philosophy.org/index.php

- What it is Like to Be a Woman in Philosophy: https://beingawomaninphilosophy.wordpress.com/

- Blog About Being a Woman in Philosophy: https://whatweredoingaboutwhatitslike.wordpress.com/

- Project Vox: https://projectvox.org/about-the-project/

Race

- Society of Young Black Philosophers: https://www.facebook.com/home.php?sk=group_313902619150

- Being a Philosopher of Colour:https://beingaphilosopherofcolor.wordpress.com/

Non-European

- A History of Philosophy in India: https://www.historyofphilosophy.net/india

- A History of Philosophy in Africa: https://historyofphilosophy.net/africana-philosophy

- A History of Philosophy in the Islamic World: https://historyofphilosophy.net/islamic-world

- Latin American Philosophy: http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195396577/obo-9780195396577-0242.xml

Indigenous Peoples

- CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory: https://www.caut.ca/content/guide-acknowledging-first-peoples-traditional-territory

- National Center for Truth and Reconciliation Reports: http://nctr.ca/reports.php

Disability

- Disabled Philosophers: https://disabledphilosophers.wordpress.com/

- PhDisabled: https://phdisabled.wordpress.com/

Teaching

- Best Practices for the Inclusive Philosophy Classroom: http://phildiversity.weebly.com/

- APA Diversity and Inclusiveness Syllabus: http://www.apaonline.org/members/group_content_view.asp?group=110430&id=380970

- Cornell Inclusive Teaching Strategies: https://www.cte.cornell.edu/teaching-ideas/building-inclusive-classrooms/inclusive-teaching-strategies.html

- Diversity Reading List: https://diversityreadinglist.org/teach/

Academic Freedom through an Equity Lens

- Daily Academic Freedom: https://dailyacademicfreedom.wordpress.com/

References

Background

Nelson, B.L.S. et al. 2018. Analysis of the ACP/CPA 2017 Equity Climate Survey.

Critical Friendship

"Critical Friend," The Glossary of Education Reform. Updated October 28, 2013. Accessed May 13, 2018. (https://www.edglossary.org/critical-friend/)

Official Multiculturalism

Foran, Charles. 2017. The Canada Experiment: Is this the World's First Post-National Country? The Guardian (January 4) https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/04/the-canada-experiment-is-this-the-worlds-first-postnational-country

The Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action Winnipeg: Manitoba. (http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf)

United Nations. 2008. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. New York: United Nations. (http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf)

Bill C-262. An Act to ensure that the laws of Canada are in harmony with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. First Session, Forty-second Parliament,

64-65 Elizabeth II, 2015-2016. (http://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/C-262/first-reading)

"Universities Canada Principles on Indigenous Education," Universities Canada. Published June 29, 2015. Accessed May 13, 2018. (https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/media-releases/universities-canada-principles-on-indigenous-education/)

Section 15 of the Charter

"Canadian Identity and Symbols" Environics Institute. Published 2010. Accessed May 13, 2018. (https://www.environicsinstitute.org/docs/default-source/project-documents/focus-canada-2010/canadian-identity-and-symbols.pdf?sfvrsn=da78fcd0_2 )

"Constitution Act 1982" Justice Laws Website Government of Canada. Modified May 4, 2018. Accessed May 15, 2018. (http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-15.html#h-45)

Implicit Bias:

Greenwald, A., D. McGhee, & J. Schwartz, 1998, "Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74: 1464-1480.

Jennifer Saul. 2013. "Implicit Bias, Stereotype Threat and Women in Philosophy" in Women in Philosophy What Needs to Change? Ed. by Katrina Hutchison and Fiona Jenkins, Oxford University Press, New York: NY. Pg 39-60.

Kelly, Daniel and Erica Roedder. 2008. "Racial Cognition and the Ethics of Implicit Bias," Philosophy Compass 3:3.

Stereotype Threat:

Schouten, Gina. 2015. "The Stereotype Threat Hypothesis: An Assessment form the Philosopher's Armchair, for the Philosopher's Classroom," Hypatia 30:2.

Steele, Claude M., Steven J. Spencer and Joshua Aronson. 2002. "Contending with Group Image: The Psychology of Stereotype and Social Identity Threat," Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 34, page 379-440.

Moral Licensing:

Monin, Benoit and Dale T. Miller. 2001. "Moral Credentials and the Expression of Prejudice," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81:1, page 33-43

Blanken, Irene, Niels van de Ven, and Marcel Zeelenberg. 2015. "A Meta-Analytic Review of Moral Licensing," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41: 4, page 540-558.

Institutional Discrimination:

Pincus, Fred L. 1996. "Discrimination Comes in Many Forms," The American Behavioral Scientist 40:2, pp. 186-194.

Epistemic injustice:

Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Medina, Jose. 2011. "The Relevance of Credibility Excess in a Proportional View of Epistemic Injustice: Differential Epistemic Authority and the Social Imaginary" Social Epistemology 25:1, pp. 15-35.

Medina, Jose. 2012. "Hermeneutical Injustice and Polyphonic Contextualism: Social Silences and Shared Hermeneutical Responsibilities" Social Epistemology 26:2, pp. 201-220.

Dotson, Kristie. 2012. "A Cautionary Tale: On Limiting Epistemic Oppression" Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 33:1, pp. 24-47.

Dotson, Kristie. 2014. "Conceptualizing Epistemic Oppression" Social Epistemology 28:2, pp. 115-138.

Intersectionality:

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics" University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 1:8, page 139-167.

Cho, Sumi, Kimberle Crenshaw and Leslie McCall. 2013. "Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis" Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38:4, page 785-810.

Tokenism:

Niemann, Yolanda. 2018. "The Social Ecology of Tokenism in Higher Education" Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice 23, pp. 451-458. (https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/tokenism)

Academic Freedom:

Dea, Shannon. 2018. "Notes from the President's Luncheon on Academic Freedom" Faculty Association of the University of Waterloo. Published March 23, 2018. Accessed May 15, 2018.(https://fauwaterloo.blogspot.ca/2018/03/notes-from-presidents-luncheon-on.html)

Challenges for Underrepresented Groups:

Haslanger, Sally. 2008. "Changing the Ideology and Culture of Philosophy: Not By Reason Alone" Hypatia 23 (2), pp. 210-23.

Dotson, Kristie. 2012. "A Cautionary Tale: On Limiting Epistemic Oppression" Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 33:1, pp. 24-47.

On Failure:

Bernard, Wanda Elaine Thomas and Bernedette Butler. "Teaching and Learning across Culture and Race: A Reflective Conversation between a White Student and a Black Teacher about Overcoming Resistance to Antiracism Practice." Understanding & Dismantling Privilege IV, no. 2 (2014): 276-297.

Harbin, Ami. 2016. Disorientation and Moral Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

In Your Own Research

Henrich Joseph, Steven J. Heine, Ara Norenzayan. 2010. "The Weirdest People in the World?" Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33:2/3, 1-75. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Research Projects with Others (Page 12):

Bunjun, Benita. The (Un)Making of Home, Entitlement, and Nation: An Intersectional Organizational Study of Power Relations in Vancouver Status of Women, 1971-2008 PhD thesis, University of British Columbia, 2011. Accessed June 21, 2018. (https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0072302)

Conferences (Page 14):

"Canadian Society for Women in Philosophy Guidelines for Conference Hosting," CSWIP Accessibility Working Group. Published 2016. Accessed May 14, 2018. (http://cswip.ca/images/uploads/CSWIP_Accessibility_Working_Group_Document.pdf)

Curriculum

Garfield, Jay and Bryan Van Norden. 2016. "If Philosophy Won't Diversify Let's Call it what it Really Is." The Stone, May 16. Accessed May 22, 2018. (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/11/opinion/if-philosophy-wont-diversify-lets-call-it-what-it-really-is.html)

Final Considerations

Grenier, Eric. 2017. "21.9% of Canadians are immigrants, the highest share in 85 years: StatsCan." CBC, October 25. Accessed June 27, 2018. (https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/census-2016-immigration-1.4368970)

Arim, Rubab. 2017. "A profile of persons with disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years or older, 2012." StatsCanada. Accessed June 27, 2018. (https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2015001-eng.pdf?st=gf16-KX4)

Acknowledgements

Although Letitia Meynell was primarily responsible for putting this document together, she did so with the support of and in consultation with numerous individuals. The efforts and insights of Tiffany Gordon and Holly Longair were particularly crucial at the beginning and end of the process, respectively. Anthony Fernandez, Tiffany Gordon, and Sarah Wieten also deserve special thanks for their presentation to the Dalhousie Philosophy Colloquium, "Developing Good Practices in Canadian Philosophy," in May 2017. Letitia also gratefully acknowledges feedback from the 2017-18 Equity Committee and the 2017-18 CPA Board and particularly thanks Jenna Woodrow, Delphine Abadie, Samantha Brennan, Christine Daigle, Shannon Dea, Andrew Fenton, Nicole Hassoun, Chike Jeffers, and Martin Pickave for their suggestions and support.

Prepared by Letitia Meynell and the Equity Committee (2017-18) of the Canadian Philosophical Association. Suggested changes or additions should be set to Letitia Meynell at Letitia,Meynell@dal.ca.

Last updated June 29, 2018.

[1] We recommend that all people teaching philosophy in Canada familiarize themselves with the Calls to Action.